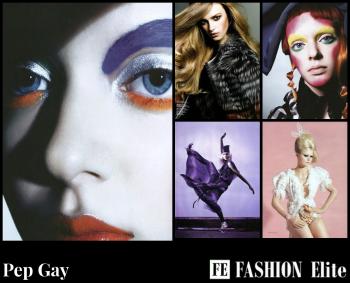

About the Make-up Artist

The first time Pep Gay went to Brooklyn, he was scared. It was 1996, and he had arrived in New York a year earlier from Spain, where he had spent his youth helping cut meat at his parents’ carnicería in Barcelona. In New York he had been so immersed in getting his career as a makeup artist off the ground that he had hadn’t really noticed that Manhattan was flanked by rivers spanned by bridges that led to other worlds. So when a friend invited him over to a loft in Dumbo, where he sublet space to sleep in a photographer’s studio, Mr. Gay accepted with some trepidation. As he walked through the industrial neighborhood on a warm summer day, the oversize scale of the factories and warehouses startled him.

And where were the gangs and the pit bulls he had seen in movies about Brooklyn?

High above, the vast arc of the Manhattan Bridge rattled as a subway train headed over it toward Manhattan. And there near the river’s edge, on Plymouth Street, was his friend’s building. In the late 19th century, it was a munitions factory, where for safety’s sake the gunpowder was kept in an annex jutting into the courtyard. Over time, the neighborhood had become so undesirable that a paper recycler had moved into the lower floors of the 200,000-square-foot building.

To get in, Mr. Gay had to thread his way around trucks waiting to disgorge their loads. Inside his friend’s decrepit third-floor loft, Mr. Gay parked himself in front of the tall windows, transfixed by the view. Powerful currents swirled the East River, and across the water, a long line of housing projects dominated the panorama of Manhattan. He was mesmerized.

“Let me know if you hear of any apartments opening in this building,” he said to his friend, as so many other New Yorkers have said to so many friends before. His friend laughed. “It’s impossible to get a space in this building,” he told Mr. Gay. Dejected, Mr. Gay returned to Manhattan and his $500-a-month studio at Bleecker and Sullivan, which he described as “the noisiest drunken intersection in the world.” But that was a step up from his first living space in New York, a $400-a-month couch in the apartment of a not-too-successful fashion model.

His thoughts kept returning to the waterfront views in Dumbo. “Growing up in Barcelona I was surrounded by water, and looking out those windows I realized how much I missed that,” Mr. Gay said. Fall arrived, then winter, and one day Mr. Gay’s friend called, his voice filled with disbelief. He had seen the single notice in his building offering to sublet a loft that he and Mr. Gay might be able to share. “Tear the sign down so no one else will see it,” Mr. Gay remembers saying. He went to his friend’s place, and they dialed the number. They heard the phone ringing in the loft upstairs and footsteps clomping over to answer it.

The woman who held the lease invited them up.

The space was a 2,500-square-foot loft, and like all the spaces in the building, it was zoned for commercial use only. But for decades, this building had been filled with residential tenants, although in a tacit “don’t ask, don’t tell” pact, the landlord and the tenants were careful never to use the words “apartment,” “kitchen” or “roommates” during lease negotiations. The woman who was subletting wanted $15,000 in “key money” to transfer the $1,400-a-month lease, which the landlord might — or might not — renew when it expired in two years. Mr. Gay, who was finding it difficult to cover his expenses, was discouraged. But the leaseholder wouldn’t negotiate. “After all,” she told Mr. Gay, “someone tore down my sign in the hallway, so there must be a lot excitement over this.”

It turned out that no one would meet her price, and three weeks later she told Mr. Gay and his friend that she would drop the demand for key money if they would tack on an extra $200 a month, for a total of $1,600. They quickly agreed. “Suddenly, my monthly rent had gone from $500 to $800,” Mr. Gay said. “I don’t know how I did it, but somehow I managed to pay it.” The apartment was a like a dream. Mr. Gay loved returning to quiet Dumbo after spending the day in Manhattan applying makeup to fashion models and celebrities like Brooke Shields, Deborah Harry and Isabella Rossellini. His neighbors were mostly artists and other bohemians. He would stargaze on the roof at night and pass sunny afternoons on the riverbank.

Once a huge sack of cacao beans washed up; another time he found many little bottles of honey.

His building’s meandering hallways turned out to be catacombs of treasures. Tenants stored things in the broken-down hallways, often attaching a note saying, “Please don’t take this.” But if there was no note, the object could be yours. “Whenever I thought of something I needed, I’d find it in the building,” Mr. Gay said. Over the years he has discovered a television, tables, chairs, lumber and artwork. To shop in those early days, Mr. Gay had to walk up dark streets to Brooklyn Heights. There was no dry cleaner or shoe repair shop, let alone a sushi bar. But in the last few years Dumbo has evolved into the Brooklyn version of SoHo, with boutiques, $3 million apartments and a grocery store selling heirloom tomatoes.

Mr. Gay took over the loft’s lease after his friend moved out three years ago. But the rent has gone up steadily, along with the area’s new luxury high-rises. To cope with the increases, about three years ago Mr. Gay subdivided the loft. He kept 1,500 square feet for himself, with an extra bedroom for a roommate and a separate 1,000-square-foot rental loft next door. He did all the work himself, using many materials he found in the hallways.

But now Mr. Gay — a boyish 38, with braces on his teeth and two tiny titanium studs in one nostril — is calmly facing what many New Yorkers would consider an impending disaster: he believes he will be priced out the neighborhood. He is saving money to buy a place, but given the current prices for waterfront apartments in New York, he is resigned to giving up his valuable river view. Although the waterfront has long satisfied a deep-seated need to connect with nature, he hopes to find a garden where he can meditate.But it won’t be a pioneering location in the next undiscovered neighborhood because, he says, there aren’t any left.

Courtesy of http://www.nytimes.com